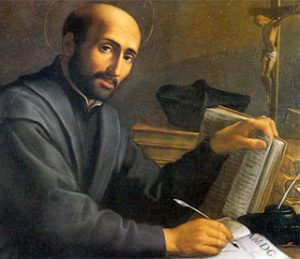

1491 — 1556

Hundreds of them were crucified in Nagasaki, 1597. Ironically, crucifixion as a means of execution was unknown to the Japanese prior to the Jesuit missions that acquainted them with the story of Jesus. Still, the Jesuit missioners were undeterred. They returned to Japan, only to be beheaded and burnt in 1622. Two members of the order, Fathers Brebeuf and Lalemant, would suffer a similar death (1649) as missioners in southern Ontario.

Loyola’s student days left him with a reputation for little more than gambling, womanizing, brawling. Student frivolity soon gave way to near-lethal seriousness, however, when French forces assaulted the Spanish city of Pamplona. Loyola was crumbled by gunshot wounds that smashed his right leg and left gaping flesh wounds in the left. French surgeons dressed his wounds and set the leg. Nine months later his limb was found to have healed improperly. The leg was broken and re-set — all without benefit of anaesthesia. Soon a grotesque projection appeared at the site of the break. Loyola knew that such a disfigurement would disqualify him for all the knightly pursuits necessary for wooing upper-class women. (At the very least he couldn’t wear the skin-tight breeches and boots favoured by courtiers.) Whereupon the vain man agreed to a third operation despite the warning that the pain of having the projection sawn off would be indescribable.

As he recovered he cast around for the adventure-tales he had always devoured. Finding none, he put up with the two books given him: a life of Jesus and the lives of the saints. Among the latter Francis of Assisi electrified him, especially Francis’s love of singing and dancing, the fact that a major illness had been the occasion of God’s changing him from vain worldling to cheerful evangelist, his transparent life embodying his announcement of grace. All of it enthralled the pain-ridden convalescent.

Gradually Loyola’s vocation seeped into him — and then surged over him as a vision (the first of many he was to have) surrounded him with a presence, the presence, and filled him with loathing for his dissolute life. There would be no turning back. Out of his new-found peace and his reflection on the life-altering event came the seeds of his Spiritual Exercises, the small book that would thereafter lend shape and substance to the spiritual direction (discerning and magnifying the work and will of God in a fellow-Christian) for which Jesuits are known everywhere. Loyola had demonstrated his uncanny perception of the subtleties and subterfuges of humankind’s heart, as well as means to exploring, exposing and neutralising them.

His heart aflame now, Loyola knew he must also attend to his head if he were going to be of greatest Kingdom-service. He enrolled at the University of Barcelona, supported by wealthy women who recognized his vocation and wanted to assist him with it. (Their precedent was the wealthy women in Jerusalem who funded Jesus and the twelve in their apostolic endeavours. Luke 8:3)

In view of his frequent visions he was suspected of being among the “illuminists” whose private scintillations lifted them (they thought) above scripture, the tradition of the church, and even elemental morality. The Inquisition had him imprisoned until he could be tried. Four months later he was acquitted, yet told as well not to gather people publicly for instruction until he had completed another four years of study.

Invariably he attracted to himself men of extraordinary gifts and dedication. In addition his unselfconscious godliness ignited his fellows (“Ignatius” means “born of fire”) as they found him larger, greater, more impressive, and vastly more influential than anything he penned. In the words of the apostle Paul, Loyola himself was the letter the Spirit wrote.

At the age of 31 he graduated 30th in a class of 100 at the University of Paris. He would never be a theological giant. A spiritual colossus, however, his major gift was his laser-penetration of the heart of those offering themselves for the company of the Jesuits. His motivation was simply the salvation of men and women anywhere. His method included outdoor preaching to large crowds who found the Spaniard unpolished, speaking poor Italian, yet simple, direct, transparent as he fused the Word of God to the word of earth. Never one to preen himself, he worked quietly in the hospitals sweeping floors, making beds, emptying bedpans and burying the dead. (The hospitals were stretched on account of two “new” diseases, typhus and syphilis.) Disgusted at the church’s practice of licensing brothels, he struggled to rehabilitate as many prostitutes as possible, accommodating them in a house where they could be educated and prepared for marriage. Alarmed at the vulnerability of Jews in Rome, he protected them relentlessly and endured the wrath of the anti-semites.

When he was 50 the pope (after years of scepticism) officially recognized the “Society of Jesus”. Loyola was elected unanimously as its superior. As head he insisted on a four-year university course in the humanities followed by seven years of intense study in philosophy and theology, together with rigorous physical training (since Jesuits would face the severest physical challenges), and before any of this a searching assessment of candidates’ suitability.

Before he died six years later there were 240 Jesuit missioners in India, Brazil and Africa, as well as five Jesuit centres in Japan. Sixty years after his death there were 15,000 Jesuits at work throughout the world.

Protestants who are perplexed at the many visitation-visions that formed him, informed him and sustained him have yet to come to terms with the same in St.Paul: the Damascus road episode, his being “caught up to the third heaven” where he heard and saw “what may not be uttered”, his vision of the man from Macedonia requesting help, his trance in Jerusalem in which he was told to leave the city.

Nothing was dearer to Ignatius than the Jesuit order. Yet when he was asked how he would react if a hostile pope were to disband it he replied, “Two hours on my knees and I should never think of it again.”

The little Spaniard known for his laughing eyes exemplified the apostle’s word, “It is no longer I who live, but Christ who lives in me.” (Galatians 2:20)

Victor Shepherd