1494 – 1536

I: — He was not someone who made trouble for the sake of making trouble. Neither did he have a personality as prickly as a porcupine. He didn’t relish controversy, confrontation and strife. Nonetheless, he was unable to avoid it. At some point he became embroiled with many of England’s “Who’s Who” of the sixteenth century. Anne Boleyn, one of Henry VIII’s many wives, flaunted her notorious promiscuity — and Tyndale called her on it. Thomas Wolsey, cardinal of the church and sworn to celibacy, fathered at least two illegitimate children — and drew Tyndale’s fire. Thomas More, known to us through the play about him, A Man For All Seasons, advanced theological arguments which Tyndale believed to contradict the kingdom of God and imperil the salvation of men and women — and Tyndale rebutted him bravely.

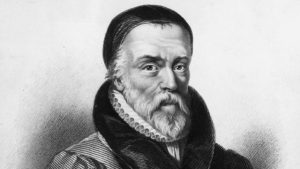

William Tyndale graduated from Oxford University in 1515, and then moved over to Cambridge to pursue graduate studies, Cambridge being at that time a hotbed of Lutheran theology and Reformation ferment. As he was seized by that gospel which scripture uniquely attests, Tyndale became aware that his vocation was that of translator; he was to put into common English a translation of the bible which the public could read readily and profit from profoundly. There was enormous need for him and his vocation, as England was sunk in the most abysmal ignorance of scripture. Worse, the clergy didn’t care. Tyndale vowed that if his life were spared he would see that a farmhand knew more of scripture than a contemptuous clergyman.

But of course his life would have to be spared. The church’s hierarchy, after all, had banned any translation of scripture into the English tongue in hope of prolonging the church’s tyranny over the people. Tyndale wanted only a quiet, safe corner of England where he could begin his work. There was no such corner. He would have to leave the country. In 1524 he sailed for Germany. He would never see England again.

Soon his translation of the New Testament was under way in Hamburg. A sympathetic printer in Cologne printed the pages as fast as he cold decipher Tyndale’s handwriting. Ecclesiastical spies were everywhere, however, and in no time the printing press was raided. Tipped off ahead of time, Tyndale escaped with only what he could carry.

Next stop was Worms, the German city where Luther had debated vigorously only four years earlier, and where the German reformer had confessed, “Here I stand, I can do nothing else, God help me!” In Worms Tyndale managed to complete his New Testament translation. Six thousand copies were printed. Only two have survived, since English bishops confiscated them as fast as copies were ferreted back into England. In 1526 the bishop of London piled up the copies he had accumulated and burnt them all, the bonfire adding point to the sermon in which he had slandered Tyndale.

Worms too was a dangerous place in which to work, and in 1534 Tyndale moved to Antwerp, where English merchants living in the Belgian city told him they would protect him. (By now he had virtually completed his translation of the entire bible.) Then in May, 1535, a young Englishman in Antwerp who needed a large sum of money quickly to pay off huge gambling debts betrayed Tyndale to Belgian authorities. Immediately he was jailed in a prison modelled after the infamous Bastille of Paris. The cell was damp, dark and cold throughout the Belgian winter. He had been in prison for eighteen months when his trial began. The long list of charges was read out. The first two charges — one, that he had maintained that sinners are justified or set right with God by faith, and two, that to embrace in faith the mercy offered in the gospel was sufficient for salvation — these two charges alone indicate how bitter and blind his anti-gospel enemies were.

In August, 1536, he was found guilty and condemned as a heretic — a public humiliation aimed at breaking him psychologically. But he did not break. Another two months in prison. Then he was taken to a public square and asked to recant. So far from recanting he cried out, “Lord, open the King of England’s eyes!” Immediately the executioner strangled him, and the firewood at his feet was ignited.

His work, however, could not be choked off and burned up. His work thrived. Eventually the King of England did approve Tyndale’s translation, and by 1539 every parish church was required to have a copy on hand for parishioners to read.

Tyndale’s translation underlies the King James Version of the bible. Its importance cannot be exaggerated. A gospel-outlook came to penetrate the British nation, its people, its policies, and its literature. Indeed, the King James Version is precisely what Northrop Frye came to label “The Great Code”, the key to unlocking the treasures of English literature, without which key the would-be student can only remain mystified and ignorant. More importantly, however, the translation of the bible into the English tongue became the means whereby the gospel took hold of millions.

Tyndale’s promise was fulfilled. He was spared long enough to see the common person know more of God’s Word, God’s Truth and God’s Way than a contemptuous clergy. In the history of the English-speaking peoples Tyndale’s work is without peer.

II:(A) — Why did Tyndale do it? Was he a ranting bible-thumper akin to the ranting bible-thumpers who put you off as readily as they do me? There is no evidence that T. was anything like this. Did he then believe something bizarre about the bible, akin to what Joseph Smith claimed for the original gold plates of the Book of Mormon? Joseph Smith, the father of Mormonism, maintained that he was sitting under a tree when there descended to his feet the gold plates inscribed with the Book of Mormon. There isn’t a person in this room who believes that that, or anything like it, happened. Neither did T. believe anything like it about scripture.

Then why was he willing to make the sacrifice he did — himself? Because he knew two things. One, he knew that intimate acquaintance with Jesus Christ matters above everything else. Two, he knew that scripture is essential to our gaining such knowledge of our Lord. Concerning T. himself there was nothing fanatical, silly, or unbalanced.

Since a preacher’s work is done under the public eye as the work of few others is done under the public eye, the preacher’s weaknesses, pet peeves, idiosyncrasies, hobby horses and neuroticisms cannot be hidden. Many of you have known me for a decade. And therefore my oddities are more evident to you than they are even to me. Nevertheless, I don’t think I appear like a ranting bible-thumper. Neither, I trust, do I appear to be fanatical, silly or unbalanced; I am like T. in this respect. Like him too in another respect: I agree that intimate acquaintance with Jesus Christ matters above everything else, and that scripture is essential to this engagement.

(B) — And so scripture is read in church every Sunday, and I read it at home every day. Once in a while someone asks me why we don’t set scripture aside in public worship and read something edifying; specifically, something that is religiously edifying. To be sure, there is much that is religiously edifying and could therefore be read with profit: the prayers of Peter Marshall, a biography of Mother Teresa, a history of the Reformation, the poetry of Madeleine L’Engle. The material is inexhaustible. Yet however edifying these edifying discourses may be, they do not supplant scripture. Why not? Because the role of scripture as witness to God’s presence and activity is unique, irreplaceable, and essential.

I want you to imagine yourself a curious by-stander, one of dozens in a crowd, listening to Jesus in the days of his trampings-about in Palestine. As he speaks you find that his teaching has the “ring of truth” about it. Your scepticism and doubt are dispelled. You are inwardly compelled to say “yes” at the same time as you own it freely. Then as the Nazarene invites you to become a disciple you step ahead, ignoring snickers and sneers as well as quizzical looks and sidelong glances. As your life unfolds in the company of Jesus Christ all that you gain from his proximity goes so deep in you that you are now possessed of ironfast assurance concerning him, his truth, his promises, his way, and his future (which, of course now has everything to do with your future). He calls other people into his company; the band swells of those who are possessed of like experience, like conviction and like satisfaction.

After Jesus is put to death and then raised from the dead none of this is lost. The ascension of our Lord doesn’t mean that those who knew him so very intimately are now left with aching emptiness and devastating disillusionment. On the contrary those who kept company with him in the days of his earthly ministry still do. To say he is ascended is not to say he is absent; to say he is ascended, rather, is to say that he is now available to everyone, available on a scale that wasn’t possible in the days when he couldn’t be found in Bethany if he happened to be in Jerusalem.

Nonetheless there is one crucial difference in the manner in which Jesus Christ is known following his ascension. Following his resurrection and ascension Christian spokespersons preach in his name, always and everywhere pointing to him. They are not he. They are never confused with their Lord. They merely point to him. They are witnesses.

And then something wonderful happens. As they point to him, as they bear witness to him, God owns their witness and his Spirit invigorates it. As witness to Jesus Christ is honoured by God, Jesus himself ceases to be merely someone pointed to; now he himself comes forth and speaks, calls, persuades and commissions exactly as he did in the days of his flesh. As witness to him is honoured by God, he ceases to be merely someone spoken about, and instead becomes the speaking, acting, impelling one himself. Now people without number in Rome and Corinth and Ephesus, people who had no chance of meeting him in the days of his earthly ministry simply because he never travelled to those cities; these people now meet him and know him and walk the God-appointed way with him as surely as did those who saw him in Bethany and Jerusalem years earlier.

Let me repeat. The apostles are spokespersons for our Lord who point to him. They do not point to themselves. Like John the Baptist they point away from themselves to him. They are witnesses. And by the hidden work of God their witness to him becomes the means whereby he imparts himself afresh. Those who have been listening to the apostles, assessing what Peter, Paul and John have to say, are startled as they realize that the issue is much bigger. Far more is at stake. They now know themselves invited, summoned even, to the same intimacy, self-forgetfulness and obedience that Peter, Paul and John have known for years. In other words, the distinction between hearing about Jesus Christ and meeting him has fallen away.

But Christian spokespersons or apostles do not live for ever. As it becomes obvious that history will continue to unfold after the apostles have breathed their last breath, their testimony written is treasured. Their testimony written now functions in exactly the same way as it used to function spoken. In other words, as the apostolic testimony written is owned and invigorated by God, men and women who read it find themselves acquainted with the selfsame Jesus Christ.

The bible is not a book of biology or astronomy or chronicle-exactness. It is the prophetic-apostolic testimony to Jesus Christ. He and it are categorically distinct, never to be confused. At the same time, knowledge of it and knowledge of him can never be separated, for he has chosen to use the witness to him as the means whereby he gives himself to us, speaks to us, and convinces us of his will for us and his way with us.

If you wanted to explore the heavens, the truth and wonder of the stars, you would get yourself a telescope. You would not waste time debating whether you should have a telescope; far less would you waste time on whether the telescope should be black or brown, handsome or ugly. Above all, you would never look at the telescope hour after hour, complaining that you had looked at it for so long and still knew nothing about the stars. You would look through it. In looking through it you would demonstrate that you understood how it functioned. And your hunger for knowledge of the heavens would be met. Scripture is not something we look at. To look at it is to be left with nothing more than another book about antiquity. We are to look through it. Insofar as we look through it the nameless longing we all have will be met, just because our Lord himself will be ours.

I know why Tyndale did what he did, why he had to do it. I trust that you know too.

Victor A. Shepherd

December 01, 1991