Home » Articles posted by Victor Shepherd (Page 12)

Author Archives: Victor Shepherd

Martin Niemoeller

1892-1984

“Is Hitler a great man?” Niemoeller’s frightened wife, Else, asked him. “He is a great coward,” her husband replied. Then Niemoeller warned her that Hitler would certainly hound and brutalize him, for Niemoeller had that day contradicted the Fuehrer at a public meeting. That evening the secret police raided and searched the Niemoeller home. A few days later a bomb exploded their home, setting it on fire. Friends offered to smuggle him and his family to Sweden, a neutral country. He declined.

Niemoeller’s dramatic confrontation with the most powerful and evil man in Europe had been foreshadowed years earlier in the claustrophobic confines of a submarine. He and his fellow officers of the World War I U-boat he captained were debating the horrors of warfare. Niemoeller said he saw at this moment – January 25, 1918 — that the world is not a morally tidy place; the world is not guided by moral principles; neutrality in the world’s struggle is not possible. At the same time, those who uphold the right are scarcely without fault themselves. The submarine commander jotted in his diary, “Whether we can survive all trials with a clear conscience depends wholly and solely on whether we believe in the forgiveness of sins.”

Soon this naval officer, who had wanted since childhood to be a seafarer, followed his father’s footsteps into the Lutheran ministry. His first parish, in the heart of an urban slum, could not pay him enough to support his family. Carefully his wife picked the gold lace off his uniform and sold it to a jeweler. His naval officer’s pension, devalued many times over on account of the collapsing German economy, purchased only half a loaf of bread. Years later he wrote, “I discovered and still know what it feels like to have no fixed employment and means of existence and sustenance.”

Hitler soon took the nation by storm. He promised to rebuild the economy, restore people’s pride, overturn their national humiliation, and eliminate the rampant immorality in the larger cities. It is little wonder that people supported him. It is greater wonder that Niemoeller did not.

Niemoeller soon discovered that Hitler was distorting the Christian faith in order to use it in the service of political power. Hitler ordered pastors to read a proclamation of thanksgiving to their congregations, a proclamation praising the government for assuming “the load and burden of reorganizing the church.” Niemoeller refused. He realized that Hitler merely wanted to use the church politically, thereafter leaving it to rot “like a gangrenous limb.”

Soon Hitler used a decree that targeted pastors of Jewish ancestry. They were to e removed from their pulpits. Of the 18,000 Protestant pastors in pre-war Germany, only twenty-three were of Jewish descent. Yet the anti-semitic hatred of the Nazi party was so intense that even this small number could not be tolerated. The machinery of the state was mobilized to eliminate them.

Because of the opposition to official policies the government informed Niemoeller in November, 1932, that he had been “permanently retired.” His congregation assumed a difficult but courageous position; they informed the government that their pastor would continue to shepherd them. Two days later at a rally in a sports stadium a featured speaker shouted, “If we are ashamed to buy a necktie from a Jew, we should be absolutely ashamed to take the deeper elements of our religion from a Jew.” “Positive Christianity,” as the state church called its propaganda, had clearly repudiated Jesus Christ.

Harassment of pastors continued. Niemoeller steamed, “It is dreadful and infuriating to see how a few unprincipled men who call themselves ‘church government’ are destroying the church and persecuting the fellowship of Jesus.”

In July 1937 the secret police arrested Niemoeller. Already he had been to prison five times, and on each of those occasions he had been released within a day or two. He expected the same quick release this time. He was wrong. The next eight years found him behind bars, the personal prisoner of Hitler himself.

On his admission to the Berlin prison he was approached by the prison chaplain, a man Niemoeller recognized form his naval days and now know as a Nazi stooge. “Pastor Niemoeller,” the chaplain said, “why are you in prison?” Niemoeller stared back at him and asked, “Why are you not?

From Berlin he was sent to Sachsenhausen, a concentration camp. He asked for, and had returned to him, two possessions dear to him – his Bible and his wedding ring. While he was in solitary confinement and not permitted to converse with anyone, the only sounds he heard were the outcries of men undergoing torture.

At home Else suffered a nervous breakdown. She and the seven children were expelled form the manse and were left with neither income nor accommodation.

Niemoeller was transferred in 1941 from Sachsenhausen to Dachau. Four years later, in April 1945, he was taken to northern Italy for execution. Three days later, American forces liberated the area and took Niemoeller in their care. They found him in poor condition – exhausted, scrawny and tubercular.

In June 1945 he was reunited with his wife. While struggling with his own personal trials he had supported thousands more with his letters, coming back again and again to the work given to God’s people through Joshua 1:9: “Be strong and of good courage: be not frightened, neither be dismayed. For the Lord your God is with you wherever you go.”

After the war Niemoeller continued to work on behalf of the devastated people of Germany. International honours were accorded him. Yet whenever asked how he wished to be introduced, he invariable replied, “I am a pastor.”

A few days before his death he remarked, “When I was young I felt I had to carry the gospel. Now that I am old I know that the gospel carries me.”

Victor Shepherd

Maximilian Kolbe

1894 –1941

Raymund Kolbe was born in a village outside Lodz , part of Poland ruled by Czarist Russia. (Since the 18th century Poland had been divided among Austria , Russia and Prussia .) His father scrabbled to feed the family through weaving, his mother through midwifery. Formal education was beyond the reach of all but the most affluent. Not surprisingly 70% of the people in Kolbe’s part of Poland were illiterate.

Kolbe’s parents were doing their best to “home school” their precocious youngster when a priest noticed the boy’s intellectual gifts and began teaching him Latin. The priest unearthed resources that moved Kolbe into a Russian school in Poland where the curriculum and ethos permitted only Russian history, culture and language.

Soon the Franciscan Order, ever alert to young men who might be called to the priesthood, had him studying at its seminary in Lwow. Here the young student was re-named “Maximilian” after the 3rd century Christian, a Roman citizen from Carthage , who had been martyred for insisting that obedience to Jesus Christ superseded obedience to the state.

Krakow was the next stop. Here Kolbe studied philosophy, journeying afterwards to Rome where he immersed himself in advance theology and philosophy at both the Gregorian College and the Franciscan.

While he was in Rome the first symptoms of tuberculosis, a disease that would torment him the rest of his life, appeared. His bodily ailment, however, disturbed him far less than the vulgar anti-Catholicism whose virulence was actually an obscene vilification of the Christian faith, of the Church, and of him who is Lord of Church and faith. Heartbroken rather than angry, he dedicated himself to the recovery of “converts” to unbelief who were avowedly hostile to the gospel. Like Loyola (founder of the Jesuit Order in the 16th century) before him who had begun with six Spaniards in fulfilment of a mission they owned together, Kolbe gathered seven young Poles who remained undeflectable in their “yes” to a vocation they couldn’t deny.

At the end of World War I the Treaty of Versailles restored Poland to nationhood. Without hindrance now Kolbe could teach philosophy and Church History in Krakow — in the Polish language. Aware, from his wide exposure to people in Rome, Poland, and Russian-occupied territories that the Church had to relinquish its religious “code words”, and aware as well that military chaplains had found combatants to be unacquainted with the elemental Christian truths despite their having been raised in “Christian” Europe, Kolbe decided to publish a magazine that would communicate the gospel in popular idiom. He begged on the streets until he had raised the start-up money. In January 1922 there appeared 5000 copies of the first edition of “Knight of the Immaculate.” It aimed at re-quickening gospel conviction in people who had deliberately or witlessly embraced secularism. Tirelessly he reiterated the motif that had threaded Wesley’s work 150 years earlier: none but the holy will be ultimately happy. In four years the magazine was printing 60,000 copies. (Eventually it would expand to 230,000. Nine different publications would appear, from a journal in Latin concerning the spiritual formation of priests to an illustrated sporting magazine.)

Young men, knowing that humanism held no future for them in the wake of the unprecedented “cultured” slaughter just concluded, flocked to the Franciscan Order as its conviction of the gospel and its vision of a Kingdom-infused society ignited them. While the “publishing community” had initially numbered two priests and seventeen lay brothers, it soon included thirteen priests and 762 brothers. It had “sprouted and grown, no one knowing how” (Mark 4:22 ) into the largest Roman Catholic ordered community in the world. Every member was accomplished in a trade or a profession, and thereby able to lend support through gainful employment. The men made their own clothes, built a cottage, provided physicians for a 100-bed hospital, and operated a food processing plant.

In September 1939 Germany invaded Poland from the west. Russia attacked from the west. Kolbe’s community was overrun with refugees. In it all he remained iron fast in his convictions: Truth is unbreakable and therefore we need not fear for it; evil, while undeniable on the macro scale (Nazism and Communism left no doubt), always had to be identified and resisted on the micro scale, for the evil “out there” also courses through every last individual human heart. The most significant battles in the universe occur there — as Solzhenitsyn was later to remind millions.

The Gestapo (German secret police) arrested Kolbe in February 1941. By May he was in Auschwitz . The “Final Solution” concerning Jewish people was still a year away. Until then Auschwitz was officially not an extermination camp but “merely” a forced labour camp whose force killed thousands nonetheless. First the inmates were dehumanized. When they had been rendered sub-human, guards felt justified in treating them like vermin. The dehumanization included identifying prisoners not by name but by number. Kolbe’s number, 16670, was tattooed into his arm. Priests especially were targeted, deemed to be only “layabouts and parasites.”

When a weakened Franciscan collapsed under his load, the tubercular Kolbe attempted to help. He was kicked repeatedly in the face, lashed 50 times, and left for dead. Recovering sufficiently to be reassigned, he used his paltry bread ration for celebrating mass. He helped a younger priest carry to the camp crematorium the mutilated bodies of those who had been tortured hideously. By now men were breaking down, throwing themselves on electrified fences or drowning themselves in latrines.

Occasionally someone managed to escape. Nazi response was swift and sure: for every inmate who escaped, ten would die slowly, agonizingly in underground, airless, concrete bunkers. On one occasion eight men had been selected when the ninth cried out that his wife and children would never see him again. Kolbe offered himself as substitute. He joined the other nine in the bunker. After two weeks four men remained alive, albeit semi-suffocated. They were injected with carbolic acid. Kolbe’s friends tried to spare his remains incineration. They failed, and had to watch the ashes blow over the countryside.

Years later, when Kolbe’s name was advanced as a candidate for canonization, Bishop Karol Wojtyla of Krakow (know today as Pope Paul II) was asked for a relic, a piece of a martyr’s body. He replied that all he could furnish was “a grain of Auschwitz soil.” In 1982 Kolbe was canonized a martyr-saint.

William Styron, author of Sophie’s Choice, has a character ask, “At Auschwitz , tell me, where was God?” Another character answers, “Where was man?” One man at least was at Auschwitz .

And after Auschwitz ? On the day of Kolbe’s canonization in St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome , Germans and Poles worshipped together in a service of reconciliation. One of the Poles was Franciszek Gajowniczek, the man whom Kolbe’s sacrifice had spared.

C.S. Lewis

1898 – 1963

In the Trinity term of 1929 I gave in, and admitted that God was God, and knelt and prayed; perhaps, that night, the most dejected and reluctant convert in all England. I did not see then what is now the most shining and obvious thing: the divine humility which will accept a convert on even such terms.

So wrote Clive Staples Lewis of his conversion in his autobiography, Surprised By Joy. “Dejected” and “reluctant” were true only in the sense that “Jack” (as all his friends called him) was now “defeated,” having held out against God for years. As persistently as Lewis had marshalled arguments of every kind to confirm him in his agnosticism, the Hound of Heaven had crept ever closer. Possessed of an unusual ability in philosophy, Lewis finally admitted reluctantly that the rational case for God had better philosophical support than the case against God His intellect took him to the very doorway of faith. Then he stepped ahead in the simple surrender and trust which also characterize the least sophisticated of God’s children. Lewis was “surprised” by joy. The nagging, nameless longing that had haunted him for years and that he had tried alternately to satisfy and to deny now gave way to contentment. He had been looking for his answer in the wrong place.

Ten million copies of Lewis’s books have now been sold. Universities offer courses in his vision. Reading societies devoted to his works flourish. He is esteemed as an author of children’s stories as well as adult fiction; a poet; an essayist whose mind probed the entire range of human experience; a critic of English literature; a radio broadcaster. Yet he is best known to Christians as a thinker who argued compellingly for the reality of God and the truth of the gospel. His all-time bestseller, Mere Christianity, now fifty years old, continues to excite readers with the sheer grandeur, truth, and practicality of the Good News.

Not surprisingly, his childhood was unusual. Books overflowed everywhere in his Belfast home. When little more than an infant he read constantly in history, philosophy, and literature. His mother schooled him in French and Latin. A teacher soon added Greek. At age sixteen he was sent to a school that prepared youths for university scholarships. Here he was tutored six hours every day by an agnostic who insisted that the young student think. In the providence of God, it was this agnostic’s integrity that bore fruit for the Kingdom, for it was this training in reasoning that subsequently helped untold Christians obey the command to love God with their mind.

Lewis interrupted his studies at Oxford to serve in World War I in France. There he began reading Christian thinkers whose influence never left him, men such as George Macdonald, a Scottish poet and essayist, and G.K. Chesterton, a Roman Catholic. Concerning his reading of such men Lewis later wrote, tongue-in-cheek, “A young man who wishes to remain a sound atheist cannot be too careful of his reading. There are traps everywhere . . . God is, if I may say it, very unscrupulous.”

While probing the world of literature he saw that the literary figures whose intellectual rigour he most esteemed – the great English poets Milton and Spenser, for instance — were believers. On the other hand, well-known literary figures whose work struck him as less substantial (Voltaire, H.G. Wells, George Bernard Shaw) were unbelievers. These latter “seemed a little thin; what we boys called ‘tinny’ . . . they were too simple.”

Zealous articulation of Christian truth was a rarity at Oxford, and an oddity as well. Lewis quickly became the butt of taunts and jibes. Yet no fair-minded academic could deny his intellectual power. The result was that Lewis’s reputation as a scholar and teacher inside university circles and his readership outside swelled alike.

A layman himself, Lewis was always concerned chiefly with expounding the historic Christian faith, that “deposit” (1 Tim. 6:20) of the gospel that had endured the acids of contempt, the dilution of shallow clergy and the distortion of heresy. Only the “faith once for all delivered to the saints” (Jude 3) would ever save.

A bachelor for most of his life, the fifty-eight years old Lewis surprised many when he married Joy Davidman. She had been raised by secularized Jewish parents, had entered university when only fourteen, and then had found her hard-bitten Marxist atheism yielding to the gospel. When a newspaper reporter asked her to describe her coming-to-faith she replied simply, “How does one gather the ocean into a teacup?” Her quick mind rendered her and Lewis soul-mates. “No corner of her mind or body remained unexplored,” he wrote in his anguish following her death. The death came as no surprise – he had known she was terminally ill when her married her. Nonetheless, he believed that God had given them to each other. His mourning found expression in A Grief Observed, a book that continues to bind up the brokenhearted.

A man whose humility was as genuine as his intellect was vast, Lewis knew that discipleship is a matter of faithfulness in the undramatic episodes of life: support for an alcoholic brother, patience with a querulous housekeeper, diligence in answering even silly-sounding correspondence – not to mention living off as little of his income as possible in order to give the remainder away.

C.S. Lewis died on the same day as did President John F. Kennedy and author Aldous Huxley. News of their deaths displaced his. Yet in the upside-down Kingdom of God, his significance remains inestimable.

Victor Shepherd

William Edwin Sangster

1900 — 1960

Never taken to a place of worship for the first eight years of his life, Sangster found his way into an inner-city London Methodist mission where he happily attended Sunday School for years. When he was twelve a sensitive teacher gently asked him if he wanted to become a disciple of Jesus Christ. “I spluttered out my little prayer”, he wrote years later. “It had one merit. I meant it.”

From that moment the gospel of Jesus Christ absorbed Sangster for life. Subordinate only to it was an obsession with recovering Methodist conviction and expression. Never possessed of a sectarian spirit, never a denominational chauvinist, he yet believed ardently that Methodism’s uniquenesses were essential to the spiritual health of Britain and to the well-being of the church catholic.

Military service followed, then studies in theology (with distinction in philosophy), and finally ordination. Short-term pastorates in Wales and northern England exposed him as a daring innovator and startling preacher. Never afraid of (apparent) failure, he was willing to try anything to reach the indifferent and the hostile. (Church-attendance in Britain had peaked in 1898, declining every year thereafter.) His first book, God Does Guide Us, paved the way for the second, Methodism Can Be Born Again. Now his alarm, even horror, at the careless squandering of the Wesleyan heritage was evident as he pleaded with his people and sought to draw them to the wellsprings of their denomination.

The outbreak of World War II found him senior minister at Westminster Central Hall, the “cathedral” of Methodism. The sanctuary, seating 3000, was full morning and evening for the next 16 years as Sangster customarily preached 30 to 45 minutes. As deep and sturdy below ground as Central Hall was capacious above, its basement became an air-raid shelter as soon as the German assault began. The first night was indescribable as thousands squeezed in, high-born and low, adult and infant, sober and drunk, clean and lousy. Equally adept at administration and preaching, Sangster quickly laid out the cavernous cellar in sandbagged “streets” so as to afford minimal privacy to those who particularly needed it. Sunday services continued upstairs in the sanctuary. A red light in the pulpit warned that an air-raid was imminent. Usually he chose to ignore it. If it were drawn to his attention he would pause and say quietly, “Those of a nervous disposition may leave now” — and resume the service. While his wife sought to feed the hordes who appeared nightly, he assisted and comforted them until midnight, then “retired” to work until 2:00 a.m. on his Ph.D thesis for London University. (The degree was awarded in 1943.) As space in the below-ground shelter was scarce, he and his family lived at great risk — a Times reporter interviewed him for his obituary! — for five years on the hazardous ground floor. They slept nightly in the men’s washroom amidst the sound of incessant drips and the malodorous smells. By war’s end 450,000 people had found refuge in the church-basement.

In 1949 Sangster was elected president of the Methodist Conference of Great Britain. The denomination’s leader now, he announced the twofold agenda he would drive relentlessly: evangelism and spiritual deepening. He knew that while the Spirit alone ultimately brings people to faith in Jesus Christ, the witness of men and women is always the context of the Spirit’s activity. By means of addresses, workshops and books he strove to equip his people for the simple yet crucial task of inviting others to join them on the Way. The second item of his agenda was not new for him, but certainly new to Methodist church-members who had never been exposed to Wesleyan distinctives. He longed to see lukewarm pew-sitters aflame with that oceanic Love which bleaches sin’s allure and breaks sin’s grip and therefore scorches and saves in the same instant. He coveted for his people a whole-soulled, self-oblivious, horizon-filling immersion in the depths of God and in the suffering of their neighbours.

In all of this he continued to help both lay preachers and ordained as books poured from his pen: The Craft of the Sermon, The Approach to Preaching, Power in Preaching. Newspapers delighted in his quotableness: “a nation of pilferers”, “tinselled harlots”, “the pus-point of sin”. Yet his popularity was never won at the expense of intellectual profundity. The ablest student in philosophy his seminary had seen, he yet modestly lamented that Methodism lacked a world-class exponent of philosophical theology — even as he himself appeared on an American “phone-in” television program where questions on the philosophy of religion had to be answered without prior preparation. Ever the evangelist at heart, he rejoiced to learn that two million viewers had seen the show.

Numerous engagements on behalf of international Methodism took him around the world and several times to America. While lecturing in Texas he had difficulty swallowing and walking. The problem was diagnosed as progressive muscular atrophy, an incurable neurological disease. His wife took him to the famous neurological clinic in Freudenstadt, Germany — but to no avail.

His last public communication was an anguished note scribbled to the chief rabbi as a wave of antisemitism engulfed Britain in January 1960. Toward the end he could do no more than raise the index finger of his right hand. He died on May 24th, “Wesley Day”, cherished as the date of Wesley’s “heart strangely warmed” at Aldersgate with the subsequent spiritual surge on so many fronts.

Everything about him — his philosophical rigour, his fervour in preaching, his affinity with saints who had drawn unspeakably near to the heart of God, his homespun writings (Lord,Teach Us To Pray), his genuine affection for all sorts and classes — it all served one passion and it was all gathered up in one simple line of Charles Wesley, Methodism’s incomparable hymn-writer:

“O let me commend my saviour to you.”

Victor Shepherd

Dietrich Bonhoeffer

1906 – 1945

When his paternal grandmother was ninety-one years old she walked defiantly through the cordon that brutal stormtroopers had thrown up around Jewish shops. His maternal grandmother, a gifted pianist, had been a pupil of the incomparable Franz Liszt. His mother was the daughter of a world-renowned historian; his father, a physician, was chief of Neurology and Psychiatry at Berlin’s major hospital. All of these currents – courage in the face of terrible danger, rare musical talents, and world-class scholarship – flowed together in Dietrich Bonhoeffer.

Since his family was religiously indifferent, family members were startled and amused – then incredulous – when Bonhoeffer announced at the age of fourteen that he was going to be a pastor and theologian. His older brother (soon to be a distinguished physicist) tried to deflect him, arguing that the church was weak, silly, irrelevant and unworthy of any young man’s lifelong commitment. “If the church is really what you say it is,” replied the youngster soberly, “then I shall have to reform it.” Soon he began his university studies in theology at Tuebingen and completed them at Berlin. His doctoral dissertation exposed his brilliance on a wider front and introduced him to internationally-known scholars.

In 1930 Bonhoeffer went to the United States as a guest of its best-known seminary. He was dismayed at the frivolity with which American students approached theology. Unable to remain silent any longer, he informed the pastors-to-be, “At this liberal seminary the students sneer at the fundamentalists in America, when all the while the fundamentalists know far more of the truth and grace, mercy and judgement of God.”

A gifted scholar and professor, Bonhoeffer remained a pastor at heart. By 1933 he had left university teaching behind and was a pastor to two German-speaking congregations in London, England. By now the life-and-death struggle for the church in Germany was under way. Did the church live from the gospel only, or could the church lend itself to the state in order to reinforce the ideology of the state? Bonhoeffer argued that the latter would render the church no church at all. An older professor of theology who had conformed to Nazi ideology in order to keep his job commented, “It is a great pity that our best hope in the faculty is being wasted on the church struggle.” As the struggle intensified, it was noticed that Bonhoeffer’s sermons became more comforting, more confident of God’s victory, and more defiant. The struggle was between the national church (which supported Hitler) and the “confessing” church, called such because it confessed that there could be only one Fuehrer or leader for Christians, and it was not Hitler. Lutheran bishops remained silent in the hope of preserving institutional unity, while most pastors fearfully whispered that there was no need to play at being confessing heroes. In the face of such ministerial cowardice Bonhoeffer warned his colleagues that they ought not to pursue converting Hitler; what they had to ensure was that they were converted themselves. An Anglican bishop who know him well in England was later to write of him, “He was crystal-clear in his convictions; and young as he was, and humble-minded as he was, he saw the truth and spoke it with complete absence of fear.” Bonhoeffer himself wrote to a friend about this time, “Christ is looking down at us and asking whether there is anyone who still confesses him.”

Leadership in the confessing church was desperately needed. Bonhoeffer returned to Germany in order to teach at an underground seminary at Finkenwald, near Berlin. Not one of the university faculties of theology had sided with the confessing church. Bonhoeffer commented tersely, “I have long ceased to believe in the universities.”

A pacifist early in the war, Bonhoeffer came to see that Hitler would have to be removed. He joined with several high-ranking military officers who were secretly opposed to Hitler and who planned to assassinate him. The plot was discovered in April, 1943. Bonhoeffer would spend the rest of his life – the next two years – in prison. Underground plans were in place to help him escape when it was learned that his brother Klaus, a lawyer, had been arrested. Bonhoeffer declined to escape lest his family be punished. (He was never to know that his brother was executed in any case, along with Hans von Dohnanyi, his brother-in-law.)

Bonhoeffer always knew that it is where we are, by God’s providence, that we are to exercise the ministry God has given us. His ministry henceforth was an articulation and embodiment of gospel-comfort to fellow-prisoners awaiting execution. Captain Payne Best, an Englishman, survived to bear tribute to the prison-camp pastor: “Bonhoeffer was different, just quite calm and normal, seemingly perfectly at his ease. . . . His soul really shone in the dark desperation of our prison. He was one of the very few men I have ever met to whom God was real and ever close to him.”

Bonhoeffer was removed from the prison and taken to Flossenburg, an extermination camp in the Bavarian forest. On April 9, three weeks before American forces liberated Flossenburg, he was executed. Today the tree from which he was hanged bears a plaque with only ten words inscribed on it: Dietrich Bonhoeffer, a witness to Jesus Christ among his brethren.

Victor Shepherd

Ronald A. Ward

1908 – 1986

A Tribute to a Spiritual Mentor

Ronald Ward looked at me warmly as he said earnestly, “As you know, Victor, the worst consequence of sin is more sin.” Our conversation in his living room continued to unfold throughout the afternoon. Just before I headed home he remarked in the same gentle, natural manner, “As you know, Victor, the worst consequence of prayerlessness is the inability to pray.”

While Protestants are sceptical of the aura that is said to surround the saints, I knew that I was in the presence of someone luminous with the Spirit of God. In his gracious way this dear saint generously assumed my spiritual stature to be the equal of his. It wasn’t and I knew it. Yet before him I ached to be possessed of that Reality to which he was so wonderfully transparent. Smiling kindly upon me he remarked, on another occasion in the midst of a different conversation, “If we fear God we shall never have to be afraid of him.” His unselfconscious profundity was steeped in the deepest intimacy of his life: his immersion in the God who had incarnated himself for our salvation in Jesus Christ.

Ward was a British-born Anglican clergyman, a classics scholar-turned-New Testament scholar. (He was awarded his Ph.D degree for his thesis, “The Aristotelian Element in the Philosophical Vocabulary of the New Testament.”) Upon emigrating to Canada he was professor of New Testament at Wycliffe College, University of Toronto, from 1952 to 1963. He wrote a dozen books. Long before I knew him, long before I began my own studies in theology, I heard my father speak admiringly of him. In the late 1950s Ward had preached at a noon-hour Lenten service in St.James Anglican Cathedral, Toronto, for downtown business people. My father came home astonished at Ward’s scholarship and aglow over the authenticity with which Ward spoke of his life in his Lord. On my 24th birthday my mother (now a widow) gave me one of his books, Hidden Meaning in the New Testament. The book explored the theological significance of Greek grammar.

Dull? Does grammar have to be dull? I read his discussion of verb tenses, imperative and subjunctive moods, prepositions, compound verbs; his discussion illustrated the truth and power of the gospel on page after page. Greek grammar now glinted and gleamed with the radiance of God himself. Insights startling and electrifying illuminated different aspects of Christian discipleship and inflamed my zeal every time I thought about them.

One gem had to do with the two ways in which the Greek language expresses an imperative. (The two ways are the present tense and the aorist subjunctive.) If I utter the English imperative, “Don’t run!”, I can mean either, “You are running now and you must stop” or, “You aren’t running now and you mustn’t start.” When two different gospel-writers refer to the Ten Commandments, one uses one form of the Greek imperative to express “Thou shalt not” while the other gospel-writer uses the other form. One says, “You are constantly violating the command of God and you must stop.” The other says, “Right now you aren’t violating the command of God and you mustn’t begin.” Both truths are needed in the Christian life; both are highlighted by means of grammatical precision.

Ward left the University of Toronto and found his way to a small Anglican congregation in Saint John, N.B. By now (1970) I was in Tabusintac, N.B., a 400-mile roundtrip away. Several times I sat before him, Greek testament in hand, asking him about grammatical points that had me stymied. What did I gain from my visits? Vastly more than lessons in grammar; I gained an exposure to a godliness I had seen nowhere else, a godliness that was natural, unaffected, real.

Any point in grammar Ward illustrated from the Christian life. One day I asked him about two verses in Mark where Jesus says, “If your hand causes you to stumble, cut it off; if your eye causes you to stumble, pluck it out.” The verb is skandalizein, to cause to stumble. But in the space of a few verses Mark uses two different tenses: one tense suggests completed action in the past, one occurrence only; the other tense suggests an ongoing phenomenon. When I asked Ward about it he said, “Victor, in a moment of carelessness or spiritual inattentiveness or outright folly the Christian can be overtaken by sin. Horrified he says, `Never again!’, and it’s done with. And then there’s the Christian’s besetting temptation with which he has to struggle every day.”

While Ward spent most of his adult life as either professor in a seminary or pastor of a small congregation, he was always an evangelist at heart. He conducted preaching missions to large crowds on every continent. Despite his exposure to large crowds he always knew of the need to sound the note of the gospel-summons to first-time faith within the local congregation. His conviction is reflected in the concluding paragraph of his book, Royal Theology. Here Ward speaks of the conscientious minister who prepares throughout the week that utterance which is given him to declare on Sunday. Such a minister, says Ward,

“should find that his congregation is not only literally sitting in front of him but is figuratively behind him. When he speaks of Christ there will be an answering note in the hearts of those who have tasted that the Lord is gracious. When he mentions the wrath of God they will be with him in remembering that they too were once under wrath and by the mercy of God have been delivered…. When he speaks of the word of the cross they will welcome the open secret of the means of their salvation. And when he gives an invitation to sinners to come to Christ, they will create the warm and loving atmosphere which is the fitting welcome for one who is coming home.”

Ronald Ward’s thinking invariably converged on the cross and his life always radiated from it. Thanks to him this is all I want for myself. Nothing more, nothing less, nothing else.

Victor Shepherd

March 1998

Mother Teresa

1910 –

She was born in Yugoslavia in the year 1910. Her name at birth was Agnes Gonxha Bejahiu. In early adult life she knew herself called of God to be a nun. Following her education at Loretto Abbey in Ireland she was posted to Calcutta. Her first assignment was to teach high school geography. She remained at this school as principal for several years.

At the age of thirty-six Mother Teresa became aware of what she speaks of as a “call within a call.” She now knew herself seized and summoned to work on behalf of “the poorest of the poor.” It was not the “ordinary poor” – those who could still beg, wheedle, or even thieve – whom she was called to serve. Rather, it was those whose situation was even more wretched: the dying destitute, the leper, the person whose sores are loathsome, and the most helpless and vulnerable of all, the abandoned baby.

She set about acquiring intensive nursing training. Two years later, the authorities in Rome released her from the Loretto order. At age thirty-eight she stepped out into her new life. She was all too aware that her activity would appear pathetically insignificant in the midst of the one million people who sleep, defecate and die on the pavement of Calcutta.

Many things sustain her. Her vocation – her calling – is one of them. Another is her conviction that the wretchedness all around her is the “distressing disguise” her Lord wears. (The festering wounds she and her sisters dress are to her the wounds of Jesus; every dirty infant is the Bethlehem baby who was born in conditions less than sanitary.) She is sustained too by her devotional discipline. Awake at 4:00a.m., she and her sisters pray until 6:30. Every morning there is a celebration of Holy Communion. Mother Teresa insists that if she did not first meet her Lord at worship and in the sacrament she could never see him in the most wretched of the earth.

The workday ends at 7:30 p.m. when sisters gather again for prayer. Midnight frequently finds the little woman still on her feet.

Several years ago she came across an emaciated man near death on the sidewalk. No hospital would admit him. She took him home. Soon she had gained access to an ancient Hindu temple which she turned into her ‘home for dying destitutes.” To this home the sisters bring the seventy- and eighty-pound adults who would otherwise die on the street. When Westerners scoff at the so-called band-aid treatment she gives to these people she replies, “No one, however sick, however repulsive, should have to die alone.” Then she tells whoever will listen how these people, with nothing to give and with a past which should, by all human reckoning, embitter them forever, will smile and say “Thank you” – and then die at peace. For her, enabling an abandoned person to die within sight of a loving face is something possessing eternal significance.

Of what worth, then, are the cast-off babies the sisters pick up out of garbage cans, railway stations and the gutter? Mother Teresa quietly asks, “Are there too many flowers, too many stars in the sky?”

When the stench from running ulcers embarrasses even a sick person himself as a Sister of Charity cares for him, the sister smiles as she reassures him, “of course it smells. But compared to your suffering, the smell is nothing.”

Mother Teresa reminds Christians of all persuasions of how readily we are infected with the narcissism (“me-only-ism”) of our age and with its preoccupation with ease. She forces us to face up to those New Testament passages that insist Jesus Christ is to be found in the sick and the poor, the vulnerable and the victimized (Matt. 25). Simply to think of her is to hear anew what Jesus maintains is the truth: We cannot turn our back on the wretched of the earth without turning our back on him.

Her diminutive body and her vast work (the Sister of Charity are now in 25 cities in India and in 26 countries throughout the world) illumine and magnify a glorious text of St. Paul: “For while we live we are always being given up to death for Jesus’ sake, so that the life of Jesus may be manifested in our mortal flesh. So death is at work in us, but life in you” (2 Cor. 4:11,12). In her disease-ridden environment she is plainly courting death. Yet because it is for Jesus’ sake that she is being given up to death, the life of the Risen One himself is manifested in her. And in a stunning paradox, the life of the Risen One is also manifested in the weakened men and women who are only hours from death themselves.

Mother Teresa and her sisters have proven once more what our society has yet to learn: a preoccupation with comfort does not produce comfort! Rather, we are comforted ourselves, as Paul insists in another paradox, only as we compound our suffering with the suffering of others. For in doing this we share in Christ’s suffering and therefore know the comfort only the victorious one himself can impart (2 Cor. 2).

Now eighty years old, yet as resolute as she is wizened, Mother Teresa continues to live and work in the slums of Calcutta, certain that God will permit her to die with the people she has lived among and loved for over forty years. In their fragile humanity she has discerned and embraced the Fragile One himself by whose wretchedness the world was redeemed and through whose risen life fellow-suffers are made alive forever more.

Jacques Ellul

1912 – 1994

The Frenchman’s life has continued to exemplify the manner in which the gospel frees us from convention and conformity and liberates us for a radical engagement with God and the world. A member of the underground resistance in France during the Nazi occupation, Ellul startled fellow-citizens at war’s end by acting as lawyer on behalf of the very collaborators who would have tortured and killed him had they uncovered him during hostilities. The reason he gave was that collaborators were being treated as savagely in peacetime camps as the Nazis had treated wartime resisters. An appreciative, life-long student of Marx, he yet repudiated communism: “under a facade of justice, it is worse than everything which preceded it”. A diligent member of ecumenical committees and associations, he laments that national and international councils achieve pathetically little. “This is not at all the equivalent of Pentecost”. His father was a sceptic and his mother a non-churchgoer, yet as a ten year-old Ellul came upon the pronouncement of Jesus, “I will make you fishers of men”. He spoke of it as a “personal utterance” which “foretold an event”. Shunning exhibitionism and therefore loath to publicize the details of his conversion, he nonetheless states that it was “violent” as he fled the God who had revealed himself to him. “I realized that God had spoken, but I didn’t want him to have me. I wanted to remain master of my life”.

Ellul was born among the dockworker families of Bordeaux. He distinguished himself at school. When his family needed money the sixteen year-old tutored in Latin, French, Greek and German. (His students were only ten!) At eighteen he read Karl Marx’s major work, Das Kapital, and for the rest of his life regarded Marx’s analysis of the power of money as more accurate than any other. At the same time he saw that Marx had nothing to say about the human condition. Revelation is needed for this. As a result he has been found himself unable to eliminate either Marx or scripture, and has continued to live with this tension.

Ellul claims he has been helped enormously in his discipleship by two soul-fast friends, one an atheist and the other a believer. The militant atheist has kept him honest by showing that Christians have tended to betray precisely what Jesus Christ is and brings. His believer-friend, “a Christian of incredible authenticity”, has supported and encouraged him when dispirited. “Every time his apartment door opened upon his smile it was, in my worst moments of distress, like a door opening onto truth and affection”.

In the years following the war he continued to lecture in law even as he was appointed Professor of the History and Sociology of Institutions. Through his work in this latter field he has seen that technology afflicts twentieth-century life as nothing else does. By technology he doesn’t mean mechanization or automation. (He has never suggested that a horse is preferable to an automobile.) Rather he means the uncritical exaltation of efficiency. If something can be done efficiently then these efficient means will be deployed without regard for the truth of God or the human good. Illustrations abound. One need only think of the proliferation of abortions in the wake of more efficient abortion-techniques — at the same time, of course, that fertility-enhancement is the cutting edge of medical research!

Ellul has angered many who glibly believe in inevitable human progress, and frustrated the same people when they have found him unanswerable. Propaganda, he insists, seduces people into consenting unthinkingly to the exaltation of efficiency; the mass media are the tools of propaganda — and it all creates the illusion that people are free and creative when in fact they are mind-numbingly conformed and enslaved.

Two parallel columns of books have poured from his pen: one a thorough-going sociological analysis which speaks to secularists turned off by pietistic cliches, the other a biblical exploration for earnest Christians who want to discern the Word of God in its vigour amidst the world’s illusions and distresses. The Technological Society and The Meaning of the City represent the two aspects of his mature thought.

Ellul has always insisted that the self-utterance and “seizure” of the living God frees individuals from their conformity to a world which blinds and binds, even as it renders them to useful to God and world on behalf of that kingdom which cannot be shaken. Not surprisingly, Ellul has continued to magnify the place of prayer, contending that as we pray God fashions a genuine future for humankind; indeed, God’s future is the only future, all other “futures” being but a dressed-up repetition of the Fall.

When moved at the bleakness of destitute juvenile delinquents, the university professor befriended and assisted them for years, seeking to render them “positively maladjusted” to their society. He wanted them to be profoundly helpful to it without adopting it. He has urged as much in interviews, sermons and the forty books and several hundred articles he has written. In them all he has reflected his most elemental conviction: God’s judgement exposes the world’s bondage and illusion for what they are, even as God’s mercy fashions that new creation which is the ground of radical human hope.

An old man now, Ellul insists the most important thing about him is his witness to Jesus Christ. “Perhaps through my words or my writing, someone met this saviour, the only one, the unique one, beside whom all human projects are childishness; then, if this has happened, I will be fulfilled, and for that, glory to God alone”.

Victor A. Shepherd

August 1992

(Illustration by Marta Lynne Scythes)

Thomas Torrance

1913 —

Torrance is the weightiest living theologian in the English-speaking world. His written output is prodigious. Prior to his retirement in 1979 he had authored, edited or translated 360 items; 250 have swelled his curriculum vitae since.

Born to Scottish missionaries in China, Torrance received his early education from Canadians who schooled “mish-kids” in accordance with Province of Ontario standards (and found, when political upheaval sent the 14-year old’s family home, that he was woefully deficient in Latin and Greek.)

While still an undergraduate he developed the discerning, analytical assessment of major theologians that would mark him for life. He noticed, for instance, that Schleiermacher, the progenitor of modern liberal theology (“liberal” meaning that the world’s self-understanding is the starting point and controlling principle of the church’s understanding of the faith) forced Jesus of Nazareth into an ideational mould utterly foreign to that of prophet and apostle. The result was that Schleiermacher’s “theology” was little more than the world talking to itself.

Torrance’s mother gave him a copy of Credo, Karl Barth’s exposition of the Apostles’ Creed. The book confirmed Torrance in a conviction that was gaining strength within him and would find expression in everything he wrote; namely, the method of investigating any subject is mandated by the nature of the subject under investigation. Since the nature of microbes differs from the nature of stars, the methods of microbiology and astronomy differ accordingly. Theology too is “scientific” in this sense, as the nature of the subject, the living God who overtakes a wayward creation in Christ Jesus his Son, “takes over” our understanding and forges within us categories for understanding his salvific work and a vocabulary for speaking of it. To say the same thing differently, the nature of what we apprehend supplies us with the manner and means of apprehending it. Therefore we come to know God not by “educated guesswork” or by projecting the best in our culture or by speculating philosophically; we come to know God as God includes us in his knowing (and correcting) us in Christ Jesus.

An academic prize transported Torrance to Basel. There he studied under Barth, the only Protestant theologian of our century whom the Roman Catholic Church as recognized as doctor ecclesiae, a teacher of the church universal. Auburn Seminary in upstate New York conscripted him to teach theology, only to have him resign two years later when he saw that world war was inevitable. Upon returning to Scotland he served as a parish minister until enlisting in the British Army for service in Italy. On numerous battlefields he was horrified to find dying 20-year olds, raised in Christian homes and Sunday Schools, who knew much about Jesus but connected none of it with God. What they knew about Jesus was unrelated to a hidden “God” lurking behind the Nazarene and remaining forever unknowable. Now their last hours found them comfortless. Torrance realized that the truth of the Incarnation — Jesus Christ is God himself coming among us and living our frailty and the consequences of our sin — was a truth largely unknown in the church, however much the church spoke of the Master or reveled in Christmas. From this moment Torrance knew his life-work to be that of the theologian who rethinks rigorously the “faith once for all delivered to the saints”. (Jude 3) He would spend the rest of his life fortifying preachers and pastors, missionaries and evangelists who had been summoned to labour on behalf of God’s people.

Ten years of parish work prepared him for a professorship at the University of Edinburgh. Appointed at first to teach church history, Torrance soon occupied the chair of “Christian Dogmatics”, dogmatics being the major doctrines that constitute the essential building blocks of the Christian faith. His reputation in this field recommended him as successor to Barth upon the Swiss giant’s retirement — even as political chicanery in the Swiss church and civil government scotched the placement.

Torrance’s contribution to the church’s theological understanding is huge. He introduced Barth to the English-speaking world. He apprised the Western Church, both Roman and Reformed, of the importance of the early Eastern Church Fathers, especially Athanasius. He grasped the theological genius of Calvin in a way that few others have and Calvin’s 17th century successors did not. Yet perhaps it is in the field of science that Torrance has most profoundly made his mark. While thoroughly schooled in arts and theology, Torrance spent fifteen years working relentlessly to acquaint himself with the logic of science and with contemporary physics. Two scientific affiliations have admitted him in recognition of his sophistication in this discipline.

In discussing the Incarnation, “the Word made flesh”, Torrance points out that logos, the Greek word for “word”, also means rationality or intelligibility. It means the inner principle of a thing, how a thing works. To say that Jesus is the logos of God is to say that Jesus embodies the rationality of God himself. The apostle John (John 1:1-18) insists both that Jesus Christ is the logos Incarnate and that everything was made through the word. Therefore the realm of nature that science investigates was made through the logos. Then the inner principle of God’s mind and being, the rationality of God himself, has been imprinted indelibly on the creation. In short, thanks to creation through the word, there is engraved upon all of nature a rationality, an intelligibility, that reflects the rationality of the Creator’s own mind.

Science is possible at all, Torrance saw, only because there is a correlation between patterns intrinsic to the scientist’s mind and intelligible patterns embodied in the physical world. Just because scientists themselves and the realm of nature have been created alike through the logos or word, the intelligibility inherent in nature and the intelligibility inherent in the structures of human knowing “match up.”

It all means that however much we may come to know of science, our scientific knowledge will never contradict the truth and reality of Jesus Christ; our scientific knowledge will never take us farther from God.

This is not to say that physics and chemistry and biology yield a knowledge of God. God alone can acquaint us with himself. But it is to say, Torrance exulted, that once we have come to know God through intimate acquaintance with the Creator-Incarnate, and as we continue to probe the splendour of the creation, we shall shout with the psalmist, “The heavens are telling the glory of God, and the firmament proclaims his handiwork.” (Psalm 19:1)

Victor Shepherd

August 2000

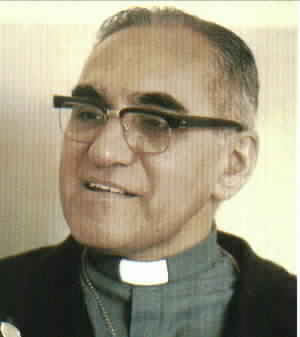

Oscar Romero

1917 – 1980

Never shall I forget the energy, zeal, knowledge and joy of the small, slender man with flashing eyes and winsome smile whom I heard speak on the University of Toronto campus in 1977. Neither could I know that I was face-to-face with someone who had been appointed, like Stephen before him, to see Jesus standing (Acts 7:56 ) as the risen Lord honours yet another martyr.

Oscar Romero was born in Ciudad Barrios, a small town in El Salvador . Longing to be a priest, he left home at fourteen as his horse picked its way to San Miguel, seven hours away, where he could begin preparing himself for his vocation.

Ordained in Rome in 1942, he was appointed in 1967 as Secretary General of the National Bishops’ Conference. His ecclesiastical career was on track. In the twenty-five years of his priesthood Vatican II (1962-65), with its plea for aggiornamento (renewal), had not impressed him. He supported the arrangement whereby the Church kept the masses credulous and docile while the aristocracy exploited them and the military enforced it all.

Coffee had been planted in El Salvador in 1828. International demand soon found private interests commandeering vast tracts of arable land while expelling subsistence farmers. By 1920 the landowning class comprised fourteen families. Dislocated peasants were now either rural serfs or urban wretched, in any case trying to live on black beans and tortillas. One-half of one per cent of the population owned 90% of the country’s wealth.

In 1932, 30,000 people died in the first uprising. Aboriginals were executed in clumps of sixty. The Te Deum was sung in the cathedral in gratitude for the suppression of “communism.” In no time El Salvador was known as yet another “security state”, a totalitarian arrangement that suspended human rights and slew internal “enemies” at will. Supporting a policy of “peace at any price”, Romero, now editor of the archdiocesan magazine Orientacion, contradicted the previous editor who had cried out against social injustice. Romero focussed on alcoholism, drug-addiction and pornography.

Then there occurred the event whose aftershocks are still reverberating through much of the world: the Council of Latin American Bishops in Medellin ( Columbia ), 1968. The Jesuits had declared their “option for the poor”, and had articulated a cogent theology that voiced their vision. They believed their theology to arise from confidence in the apostles’ witness that the Kingdom of God has come and needs to be leant visibility. A teaching order, the Jesuits schooled their students convincingly as Romero equivocated, apparently supporting “liberating education” while declaiming against “demagoguery and Marxism.”

In 1975 the National Guard raided Tres Calles, a village in Romero’s diocese. (By now he was bishop of Santiago de Maria.) The early-morning attack hacked people apart with machetes as it rampaged from house to house, ostensibly searching for concealed weapons. The event catalyzed Romero. At the funeral for the victims Romero’s sermon condemned the violation of human rights. Privately he wrote the president of El Salvador , naively thinking that a major clergyman’s objection would carry weight.

His “turn” (such an about-face scripture calls “repentance”) accelerated. Plainly the church was at a crucial point in the history of its relationship to the Salvadoran people. Would it help move them past an oppressive feudalism or retrench, thereby strengthening the hand of the oppressor?

When Romero was promoted as Archbishop of San Salvador, the capital city, the ruling alliance intensified its opposition. Six priests were arrested and deported to Guatemala . One of them remarked that the church finally was where it was supposed to be: with the people, surrounded by the wolves. Romero’s first task as archbishop was grim: he had to bury dozens whom soldiers had machine-gunned when 50,000 protesters demonstrated against rigged elections.

By now Romero had turned all the way “around the corner.” Summoning priests to his residence (he had moved out of the Episcopal palace and was bunking in a hospital for indigents) he told them he required no further evidence or argumentation: he knew what the gospel required of church leaders in the face of the people’s misery. All priests were to afford sanctuary to those threatened by government hounds.

Immediately the “hounds” sent a message to Romero as Rutilio Grande, a Jesuit friend who had struggled to implement Vatican II reforms, was gunned down in his jeep, together with an old man and sixteen year-old boy. Undeterred, Romero prayed publicly at length beside his friend’s remains, and then buried all three corpses without first securing government permission – a criminal offence. Next he did the unthinkable: he excommunicated the murderers. In a dramatic gesture he cancelled all services the following Sunday except for a single mass in front of the cathedral, conducted outdoors before 100,000 people. When he went to Rome to explain himself, the pope replied, “Coraggio – courage.” Courage? Rightwing groups were leafleting the nation, “Be a patriot: kill a priest.”

Reprisals intensified. In one village anyone found possessing a bible or hymnbook was arrested, later to be shot or dismembered. Four foreign Jesuits were tortured, their ravaged bodies dumped in neighbouring Guatemala . Thousands of people disappeared without trace. In all of this Romero never backed down: Christ is King just because he brings his Kingdom with him, and in their discernment of this reality Christians must be “fellow workers in the truth”(3rd John 3) in anticipation of “new heavens and a new earth in which righteousness dwells.”(2nd Peter 3:13)

Romero insisted that he had not warped the gospel into a program of social dismantling, let alone malicious social chaos. He criticized priests who wanted to reduce the gospel to political protest without remainder. He deplored protesters’ violence, even as he admitted they were victims of long-standing institutional violence.

International recognition mounted. 1978, 118 members of Britain’s House of Commons nominated him for the Nobel Peace Prize (awarded that year to Mother Teresa of Calcutta.) The Louvain , a prestigious Roman Catholic university in Belgium , gave him an honorary doctorate.

Knowing himself to be on the government’s “hit list,” he went to the hills to prepare himself for his final confrontation with evil. He telephoned his farewell message to Exclesior , Mexico ’s premier newspaper, insisting that like the Good Shepherd, a pastor must give his life for those he loves.

Romero was shot while conducting mass at the funeral of a friend’s mother. His assassin escaped in the hubbub and has never been found. 250,000 thronged the Cathedral Square for his funeral. A bomb exploded. Panic-stricken people stampeded. Forty died. In the next two years 35,000 Salvadorans perished. Fifteen per cent of the population was driven into exile. Two thousand simply “disappeared.”

In 1983 Pope John Paul II prayed at Romero’s grave, and then appointed as national archbishop the only Salvadoran bishop to attend Romero’s funeral. The message was plain. The pope had given his imprimatur to all that Romero had exemplified.

He has been recommended for recognition as a “saint.” All Christendom awaits his canonization.

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn

1918 —

The horror tests comprehension: citizens sentenced to internal exile, incarceration, systematic starvation, torture and death on account of casual comment; secret police calling on people who have lived for years in dread of a pre-dawn knock on the door; orphaned children roaming city streets in packs as conscienceless, desperate and dangerous as wild hyenas bent on survival; men sentenced to lethal labour in Siberia, never to be heard from or heard of again, because they had visited the west; prisoners of war who had survived Nazi death camps and thereafter had to be assigned to Soviet camps since their wartime P.O.W. experience had given them a taste of the “finer things” of bourgeois life. Stalin slew sixty million before the seventy-four year nightmare ended and the Soviet communism crumbled in 1991.

It all began in 1917. One year later Solzhenitsyn’s widowed mother gave birth to the man in whose homeland devastation careened everywhere. In 1922 four leaders of the Russian Orthodox Church were executed because they had collected funds meant to assist hunger-deranged people found eating the carcasses of children who had succumbed to malnutrition and disease. Eventually Solzhenitsyn would see first-hand the irrationality that arises whenever ideology is maintained in the face of everything that contradicts it, for he narrowly escaped arrest when others in his bread queue were imprisoned for “suggesting” that there was a bread-shortage in the Marxist land-of-plenty, and for sabotaging the state by “sowing panic.”

Solzhenitsyn’s mother, fluent in French and English, was dismissed from her position as secretary at a flourmill since her family, prior to the Revolution, had had a little more money than most. Yet the effect of her mistreatment at the hands of coercive atheism merely found faith flooding her, never to recede. A godly aunt and uncle steeped the youngster in Orthodox liturgy and devotion. They also introduced him to Russia’s literary giants, especially Tolstoy. Soon he was reading Shakespeare and Dickens in English, Schiller in German. No less adept in the sciences than he was in the humanities, Solzhenitsyn recognized nonetheless that Marxist materialism would allow him to support himself through teaching mathematics and physics while literature remained his vocation.

In 1941 the Soviet Union entered World War II. Solzhenitsyn trained as an artillery officer and was decorated for bravery. Stalin, outraged at German brutalisation of Soviet citizens, announced than when Russian forces invaded Germany “everything” would be permitted. Solzhenitsyn was sickened as the elderly were robbed of their meagre rations and women were gang-raped to death.

A few months earlier he had penned a letter to a friend in which he had likened Stalin’s rule to feudalism. The letter had found its way to government snoops who forced his commanding officer to arrest him. Made to hand over his service revolver (the sign of dismissal,) he stood degraded when his officer’s insignia was ripped off his uniform and the red star torn from his hat.

Nights now found the disgraced man lying on a prison mattress of rotten straw adjacent to a latrine bucket. Men stepped over him to use it throughout the night. A few weeks later he was moved to the dreaded Lubyanka prison in Moscow, and locked up in a windowless cell so small he couldn’t stretch out his legs whether he sat or lay down. He had been charged with producing anti-Soviet propaganda. Eventually he was transferred to one of the forced labour camps that dotted the interior of the U.S.S.R. Lubyanka was to give rise to his world-acclaimed novel, The First Circle; his labour camp existence to his three-volume Gulag Archipelago. When he was diagnosed with cancer and expected to die (surgery with only local anaesthetic removed a large tumour and kept him alive) he pondered what would later appear as Cancer Ward. Yet his years of suffering in assorted prisons and prison camps worked a triumph in him: “…I was fully cleansed and came back to a deep awareness of God and a deep understanding of life.”

His “release” after eight years’ incarceration metamorphosed into internal exile. Now he was teaching high school in the easternmost reaches of the U.S.S.R, forbidden to travel. Through it all he wrote ceaselessly on scraps of paper, squirreling them away lest he commit the same blunder that had seen him sentenced. Then in 1956 President Nikita Khrushchev, publicly faulting Stalin’s harshness, deemed Solzhenitsyn’s wartime letter non-criminal. All charges were dropped. He went home.

Invited to read two chapters of One Day to eager Muscovites, Solzhenitsyn obliged them, and then excoriated the secret police. Only his international reputation spared him. The Soviet government dared not molest someone who had been awarded the Nobel prize for literature and whose books had been translated into 35 languages in one year. Still, it banished him. He moved to Switzerland, where Gulag could be published. The U.S.A. inhaled six million copies. The New York Review of Books pronounced it the single most devastating political indictment to appear in the modern era.

Eager to escape media hounding, he moved with his family to Vermont and became a near-recluse, always writing, emerging occasionally to speak, for instance, at Harvard’s commencement in 1978. Fifteen thousand people rain-soaked people reeled as he judged the west morally destitute. President Jimmy Carter’s wife sniffed, “There is no ‘unchecked materialism’ in the U.S.A.” Solzhenitsyn’s recitation was relentless: America’s pursuit of happiness has left it intellectually shallow, ethically incoherent and spiritually destitute.

Then in 1989 the Berlin wall crumbled, one of history’s unforeseeable convolutions. Two years later communism ended in Russia. Three years later still Solzhenitsyn returned to Russia, only to find that decades of communism had weakened the people to the point that they were vulnerable to contagion from the west. The infectious disease of material greed vomited up large-scale corruption, economic chaos, and clandestine financial compromises.

Despite the sickness of his still-weak nation Solzhenitsyn’s hope is undiminished. Russia can be healed, even as he is adamant that only Christian faith can heal it. Only the crucified can quicken in Russia’s people the self-renunciation any nation needs if only because self-renunciation is life’s open secret. Aware of systemic evil and of the “powers” of ideologies and “isms,” he likes to quote the old Russian proverb: “When evil appears, don’t search the village; search your heart.” Having seen his work achieve the unimaginable, he is convinced that even those with little visibility must pursue what has sustained him: “I live only once, and I want to act in accord with absolute truth.”

As long as truth is absolute it must be uttered amidst treachery, cruelty and falsehood. As it is uttered it will prove itself pregnant and powerful. When accepting his Nobel Prize he had cried, “One word of truth outweighs the world.”

William Stringfellow

1928 – 1985

“Can the pope speak infallibly?”, Stringfellow was asked at an ecumenical gathering. He reply was swift and sure. “Any Christian who speaks in conformity to the gospel speaks infallibly.” It was typical of the pithy pronouncements which would endear him to many. Yet he was ever as profound as he was precise. When Karl Barth visited the United States in 1962 he pointed past the seminary professors to the diminutive lawyer and remarked, “This is the man America should be listening to.”

William Stringfellow was born in Johnston, Rhode Island. His father was a knitter in a stocking factory. Needing money for a university education, he held three jobs in his last year of high school, yet managed to gain several scholarships and find himself at Bates College by age fifteen. Another scholarship took him to the London School of Economics. It was here, he was to write later, that he learned the difference between vocation and career. Military service followed with the Second Armored Division of the U.S. Army. When other soldiers complained that they were deprived of an identity in the armed forces and couldn’t “be themselves”, he disagreed. He knew that it is the living Word of God, Jesus Christ, which gives us our identity and frees us to “own” ourselves, cherish ourselves, profoundly be ourselves, anywhere.

Next was Harvard Law School. While a degree from this prestigious institution was a key which unlocked many doors, the door on which he knocked belonged to a slum tenement in Harlem, New York City. He had decided to work among poor blacks and Hispanics, the most marginalized of the metropolis. The move from Harvard to Harlem was jarring. His apartment measured twenty-five feet by twelve feet. Earlier five children and three adults had lived in it. The kitchen contained a tiny sink and an old refrigerator (neither of which worked), an old gas stove, a bathtub, and a seatless toilet bowl. Thousands of cockroaches were on hand to greet him. “Then I remembered that this is the sort of place in which most people live, in most of the world, for most of the time. Then I was home.”

Stringfellow’s chief legal interests pertained to constitutional law and due process. Both were dealt with every day as he represented victimized tenants, accused persons who would otherwise have inadequate counsel in the courts, and impoverished black people who were shut out of public services like hospitals and government offices. Knowing that his Lord had touched the untouchable — lepers — he represented those who belonged to the George Henry Foundation, sex-offenders whom no other lawyer would assist.

Throughout his student days Stringfellow had involved himself in the World Christian Student Federation. Now he was as deeply immersed in the World Council of Churches, not to mention the turbulence of his own denomination, The Episcopal (Anglican) Church of the U.S. Friends insist he was never more eloquent than the night he stood up, uninvited, in the Anglican Cathedral, Washington, and pleaded with his denomination to ordain women to the priesthood. He appeared not to be heard.

Frustration with the church was not new to him. Upon moving to Harlem he had joined the East Harlem Protestant Parish, enthused by its stated commitment to honouring the witness of scripture and the vocation of the laity. Within fifteen months he sadly concluded that once again the bible had been silenced and the laity submerged. The Parish, like most churches in North America, was a clergy-controlled preserve of shallow leftist ideology. Meanwhile, denominational authorities refused to use the confirmation class book he had been commissioned to write. (The realism of Instead of Death was too startling!)

His beloved poor in Harlem continued to mirror to him the engagement of the Word of God with human anguish. “What sophisticates the suffering of the poor”, he wrote, “is the lucidity, the straightforwardness with which it bespeaks the power and presence of death among men in the world.” All men and women. He had learned from scripture that apart from the resurrected One death is the ruling power of this world, corrupting and crumbling everything its icy breath corrodes. “And from this power of death no man may deliver his brother, nor may a man deliver himself.”

His frustration with seminaries was inconsolable. Liberal schools of theology, having disdained the bible, offered little more than “poetic recitations…social analysis, gimmicks, solicitations, sentimentalities, and corn.” Fundamentalist institutions, on the other hand, had yet to learn that “…if they actually took the bible seriously they would inevitably love the world more readily…because the Word of God is free and active in the world.” As often as seminarians shunned him, students at the law schools and business schools of major American universities heard him eagerly: they were aware that he knew just how the world turns, and who or what makes it turn. So it was that he travelled easily among practising law in behalf of those who could not afford to pay, delivering a guest lecture at Columbia University Law School, preaching the good news of deliverance and reconciliation among church people across America who had no grasp of the deadly, deep-dyed racism he lived with every day. Fourteen books poured from his pen, as well as dozens of articles in both theology and law.

Raging diabetes overtook him. When he died a distraught Daniel Berrigan, Jesuit anti-nuclear protester whom Stringfellow had afforded sanctuary, could only say, “He kept the Word of God so close…and in such wise that its keeping became his own word and its keeping.” Jim Wallis, leader of the Sojourners Community in Washington where Stringfellow had spoken frequently, summarized the lawyer’s life: “In his vocation and by his example he opened up to us the Word of God.”

Victor A. Shepherd

February 1992

(Illustration by Marta Lynne Scythes)

Martin Luther King Jr.

1929-1968

He was born Michael King, but when he was five years old his father (also Michael) decided that father and son should be renamed “Martin Luther” — senior and junior. Thereafter the putative leader of the Afro-American people was known as “ML.” His intellectual precocity appeared as early as the prejudice he would have to fight all his life. For as he exuberantly awaited the end of the bus ride home following his triumph at his school’s public speaking contest, the conductor exploded, “You black sonofabitch.” King hadn’t responded instantly when the conductor told him to surrender his seat to a white rider.

When only fifteen King was admitted to Morehouse College , an all-black institution in Atlanta . He focussed on a legal career since law seemed the vehicle for addressing the shocking social inequities that were rooted in racist iniquity. Soon, however, Dr. Benjamin Mays, Morehouse’s president and King’s personal mentor, acquainted him with an expression of the Christian faith that was intellectually rigorous, socially sensitive, and ethically compelling. Determined now to be a preacher, he began theological studies at Crozer Seminary, Pennsylvania , one of the few blacks among the white student body.

Searching for the roots of injustice, King alighted on capitalism, only to see that its inherent exploitation found no correction in communism’s cruelty. Illumination flooded him the day he attended a lecture on Gandhi and understood two crucial matters: one, that only as injustice is overturned without a legacy of bitterness and festering recrimination has anything been accomplished; two, that just as non-violent protest had been possible in India thanks to British protection, paradoxically, amidst British colonialist oppression, the same non-violent protest could be effective in the USA on account of the Constitution. And just as Gandhi had insisted that the British shouldn’t be slain for exemplifying the hardheartedness endemic in humankind (Indians included,) black Americans would have to help white people save themselves from themselves. Gandhi had taken seriously Jesus’ forgiveness of enemies when British colonialists had not. King knew that we are never closer to God than we are to our worst enemy. Oppressor and oppressed were already linked in Christ.

Acclaimed Crozer’s outstanding student, King relished the scholarship Boston University ‘s School of Theology accorded him for doctoral studies. While in the north he met and married Coretta Scott, a Methodist. Declining tantalising academic positions in the north, he returned to the south to equip the people for whom he’d been anointed. As pastor of Dexter Avenue Baptist Church in Montgomery , he realized that it wasn’t enough to inform people; they had to be moved. Lecture and sermon were qualitatively distinct; the latter bore fruit only as informed minds and warmed hearts issued in wills that acted in the face of institutions and images and ideologies and “isms” still entrenched despite the Emancipation of 1863. King developed the thoughtful, persuasive rhetoric for which he became famous as alliteration and illustration and startling turn-of-phrase were found in speech patterns and word associations as unforgettable as his cadences were irresistible.

Montgomery embodied the ante-bellum myth that black people were sub-human chattels. Since few of them could afford cars, they had to ride city buses to and from work. They were never allowed to sit in the first four rows of seats. When they paid their fare at the fare box beside the driver they then had to get off the bus, walk outside to the rear, and re-enter there. Frequently the driver drove off before they’d had to time to re-board.